Achieving Health Equity

Today people are learning more and more about the inequities that BIPOC face simply because of the color of their skin. Racism impacts a person’s income, housing, employment opportunities, and health. Today we will be exploring how social determinants impact health equity.

Equity vs. Equality

Equity is the absence of avoidable or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically (WHO). Essentially equity is leveling the playing field to remove things (like race) and give everyone the help that they need to succeed. Equality is giving everyone the same level or amount of help in order to succeed. The difference between the two is best illustrated by the analogy of three people who are different heights trying to see over the fence. Equality means that they are all given the same height box to stand on. With this size box only two can see over the fence. Equity means that every person is given the box they need to see over the fence. In real life it is social determinants are what help people achieve health equity.

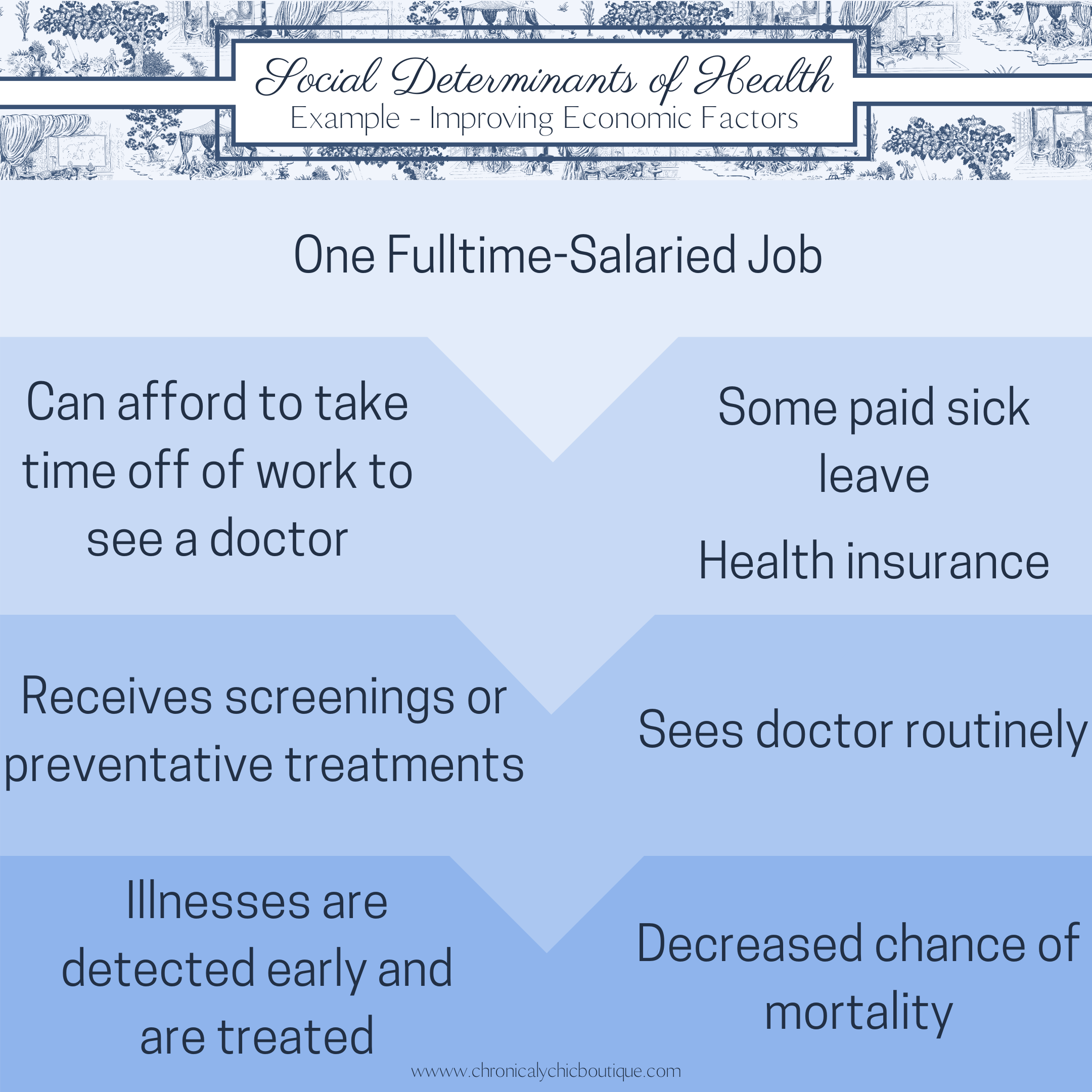

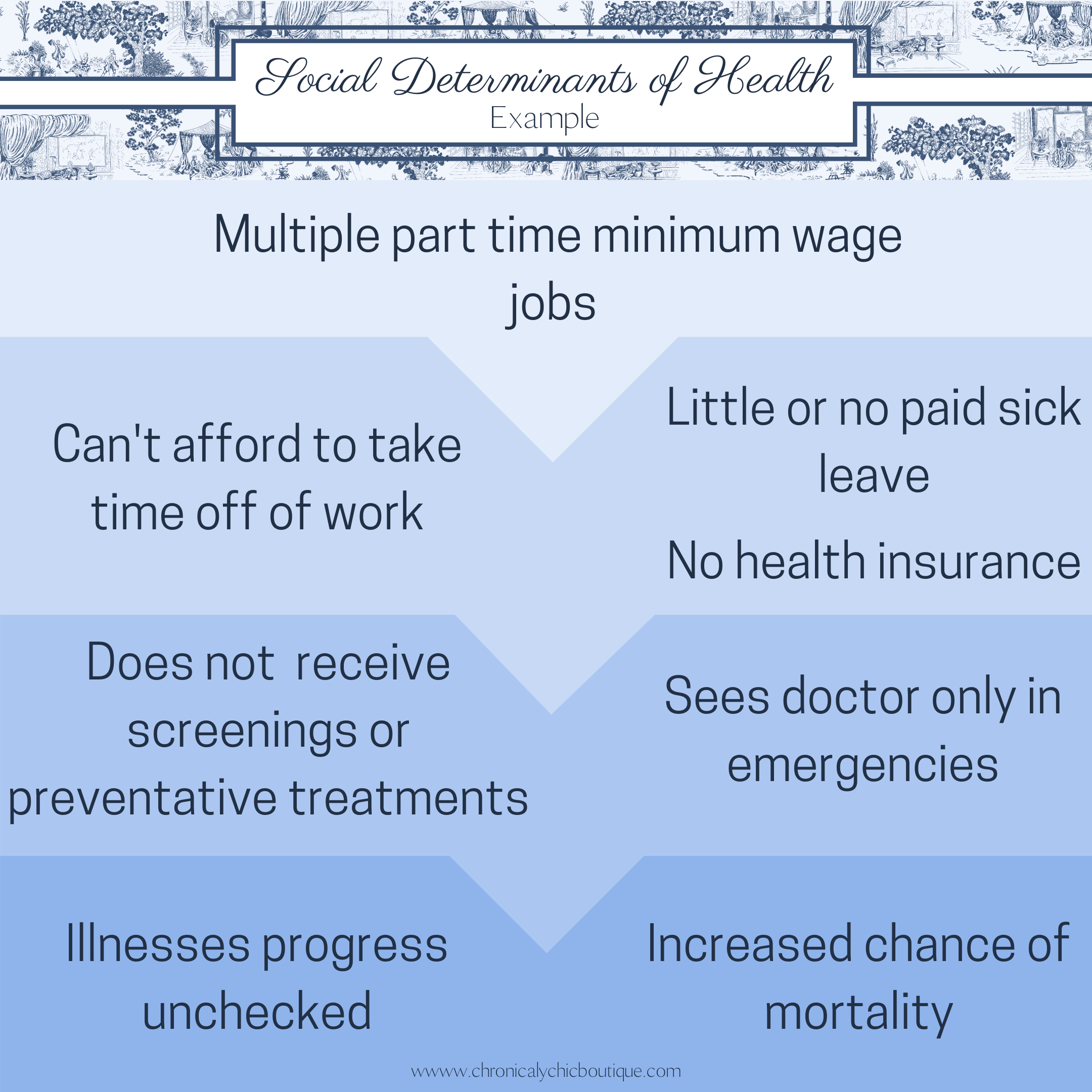

Social Determinants of Health

There is evidence that shows that “an individual’s overall health and life expectancy is determined by a variety of factors beyond biological measures and genetic code” (CDPHE 2017). The WHO defines the social determinants of health as, “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels. The social determinants of health are mostly responsible for health inequities – the unfair and avoidable difference in health status seen within and between countries”. Addressing each social determinant of health can have profound effects on individual health outcomes (Aritga 2018).

How do social determinants impact a person’s health?

Social determinants impact a person’s health in a variety of ways. If a person’s income is below the poverty line (~$10,000/year) their housing may not meet current liveable standards, the schools that are available to them may be overcrowded and underfunded, there may be fewer doctor’s servicing the neighborhood, and transportation to other neighborhoods may be limited. Each of these factors can negatively affect a person’s health in multiple ways. These social determinants of health explain why people with lower socioeconomic status (SES) have increased rates of diabetes, as well as higher death rates rates for cancer, and cardiovascular disease, and many other negative health outcomes.

Talking Headways “Episode 294 Social Determinants of Health” podcast. https://streetsblog.libsyn.com/episode-294-social-determinants-of-health

Race’s impact on a person’s health

In America race can negate any “gains” a person may have through increased wealth, higher education, safer communities, the list goes on. This is exemplified by the pregnancy-related death rate for black women. Black women have three times higher birth and pregnancy-related mortality ratios (PRMRs) compared to white women (Peterson 2019). The pregnancy-related death rate for black women is 41 per 100,000 live births, and 30 per 100,000 for American Indian/Alaska Native Women. Whereas that rate is 13 per 100,000 for white women. The PRMRs for black women with a bachelor’s degree or higher is 5.2 times that of white women with a similar education (Peterson 2019). The PRMR among black women with a completed college education or higher was 1.6 times that of white women with less than a high school diploma (Peterson 2019). These last two statistics in particular highlight that even affluent BIPOC are under increased stress from racism in their everyday lives and are still experiencing racism within the healthcare system. One example of this is tennis player Serena Williams when she almost died after the birth of her daughter. Williams’ wealth and fitness did not shield her from medical complications. She wrote an op-ed discussing her birth and how this is an all too common problem for BIPOC around the world.

Serena Williams, “What my life threatening experience taught me about giving birth” https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/20/opinions/protect-mother-pregnancy-williams-opinion/index.html

The Birth Hour – A Birth Story Podcast “What’s Behind Racial Disparities in Pregnancy and Childbirth” podcast. https://poddtoppen.se/podcast/1041801905/the-birth-hour-a-birth-story-podcast/whats-behind-racial-disparities-in-pregnancy-childbirth-denene-millner

From cancer, heart disease, diabetes and every disease in-between BIPOC are at far greater risks from these diseases than non-hispanic white people.

To explain these disparities a “weathering” hypothesis has been proposed “which posits that Blacks experience early health deterioration as a consequence of the cumulative impact of repeated experience with social or economic adversity and political marginalization” (Geronimus et al. 2006). Evidence has been found to support this hypothesis. Geronimus et al. 2006 found that blacks had higher scores than did Whites and had a greater probability of a high score at all ages, particularly at 35–64 years. Racial differences were not explained by poverty. Poor and non-poor Black women had the highest and second highest probability of high allostatic load scores, respectively, and the highest excess scores compared with their male or White counterparts. Dr. Geronimus discussed her findings on NPR’s Code Switch podcast. Click the link below to have a listen or read the transcript.

Code Switch “This racism is killing me inside” podcast and transcript. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/576818478

How do we achieve health equity?

Addressing these inequities may seem insurmountable, but many public health programs have proved to make inroads to address the inequities. The health impact pyramid is a 5-step pyramid helps describe the impact of different types of interventions (Frieden 2010). Programs that address socioeconomic factors have the broadest impact on a population. Programs on this level can address increased wages and benefits, access to better education, and improved nutrition, sanitation, and housing. These interventions can be expensive but can have far reaching impacts on people’s lives.

Health Impact Pyramid

Benjamin Franklin once said that “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” this statement still rings true today. Public health programing is an effective way of improving people’s lives and reducing health care expenditures. Masters et al. 2017 found that for every $1 spent on public health programming $14.30 was the median return on investment (ROI). They found that the most effective public health programs were legislation (median ROI=$46.50), focused on health protection (median ROI=$34.20), or programs at a national level (median ROI=$27.20).

The CDC offers tools to help communities address social determinants of health.

How can I help?

In this moment we are seeing that our voices can effect change. You can write to your elected officials on all levels expressing your support for increasing the minimum wage, making sure that education funding is divided fairly among communities, supporting organizations in your community that use preventative measures. Legislation provides the most return on investment for public health programming, so do not underestimate the power of your vote and sustained pressure on elected officials. Leave a comment about how you are working to improve equity in your community. I would love to compare notes.

Citations

1. World Health Organization. Health Systems: Equity. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/equity/en/

2. Colorado Department of Public Health (2017). CDPHE Social determinants of health meta analysis. Retrieved from: https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/sites/default/files/PSD_SDOH_Meta-Analysis_long.pdf

3. World Health Organization. Social determinants of health. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en/

4. Artiga S., Hinton E., (2018). Beyond Health Care: the role of social determinants in promoting health equity. Retrieved from: https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/beyond-health-care-the-role-of-social-determinants-in-promoting-health-and-health-equity/view/footnotes/#footnote-412056-1

5. Petersen, E. E., Davis, N. L., Goodman, D., Cox, S., Syverson, C., Seed, K., … Barfield, W. (2019). Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths — United States, 2007–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(35), 762–765. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3 Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6835a3.htm?s_cid=mm6835a3_w

6. Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores Among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2004.060749 Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1470581/

7. Frieden, Thomas R. “A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid.” American journal of public health vol. 100,4 (2010): 590-5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652 Retrieved from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2836340/

8. Masters R, Anwar E, Collins B, Cookson R, Capewell S. (2017) Return on investment of public health interventions: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2017;71:827-834. Retrieved from: https://jech.bmj.com/content/71/8/827